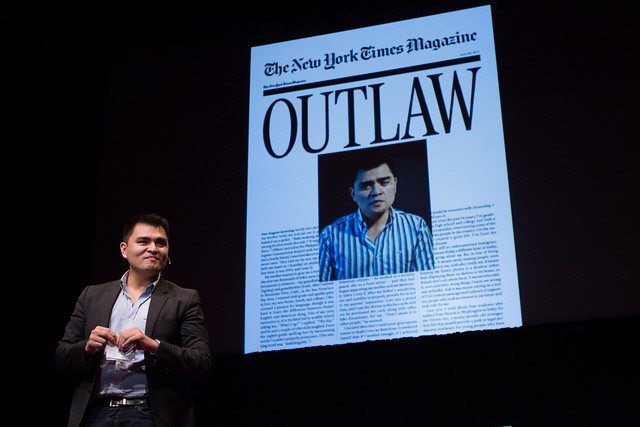

Jose Antonio Vargas has quickly become the face that has humanized the struggle for immigration reform. Unlike other immigrants, Jose is a Pulitzer Prize winning journalist, Washington Post reporter, activist, and the founder of an immigration awareness campaign called ‘Define American’. Back in June of 2011, Vargas courageously revealed to the world that he was undocumented in a column he wrote for New York Times magazine. In it he describes what his move to the United States was like, the lengths he went to as a child to fit in to the American lifestyle, and what it has been like residing in the United States unlawfully. Jose’s journey to the United States began much like that of any other immigrant. He was smuggled into the United States from the Philippines when he was only 12 years old by an individual he believed to be his relative. Once in the United States, Vargas was raised by his hardworking grandparents who afforded him a better future. From the outset, his upbringing in the bay area of San Francisco appeared to be much like that of any other American child.

It was not until he made a visit to the DMV to obtain his driver’s permit that he realized the green card he was given by his grandfather was in fact fake when he was told by the woman at the DMV window not to come back there again. For years, Jose Antonio Vargas has dedicated his life to standing in solidarity with the thousands of undocumented immigrants residing in the United States illegally. He has done this by serving as the voice of the undocumented, attending hundreds of conferences and speaking engagements, in addition to writing as a distinguished columnist.

Up until July 15th Vargas was able to advocate for the plight of undocumented immigrants without being apprehended despite constantly being in the public eye. A few days prior to July 15th Vargas appeared at a shelter housing Central American children and refugees and attended a vigil to honor them near the Rio Grande Valley. His presence in the region was meant to call attention to the humanitarian nature of the subject. In order to attend the event, Vargas crossed the McAllen, Texas TSA checkpoint, an area known to be highly secured and militarized. Vargas had not given much thought to the possible risk of being detained once he would return to the United States through the same checkpoint. According to the Department of Homeland Security Vargas was detained once he told TSA officials that he was residing in the country illegally. He was then taken to the McAllen Border Patrol Station and was given a Notice to Appear before an immigration judge. He was released within the same day after speaking with Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials. Unfortunately for Vargas, until comprehensive immigration reform is passed, he will continue to be forced to live under the radar. Vargas was not able to qualify for the Dream Act or for DACA, because his age did not meet the cutoff age as required by law. Shortly after being released Vargas issued a statement saying that the undocumented are constantly having to live in fear as a result of the failure of Congress and President Obama to act and bring about a viable solution to the problem. Jose Antonio Vargas challenges Congress to act by asking them the question: how do we define American?

Visa Lawyer Blog

Visa Lawyer Blog